When Prime Minister Mark Carney announced sweeping bail and sentencing reforms on 16th October, it felt—for the first time in a long time—like the Canadian justice system might finally be listening.

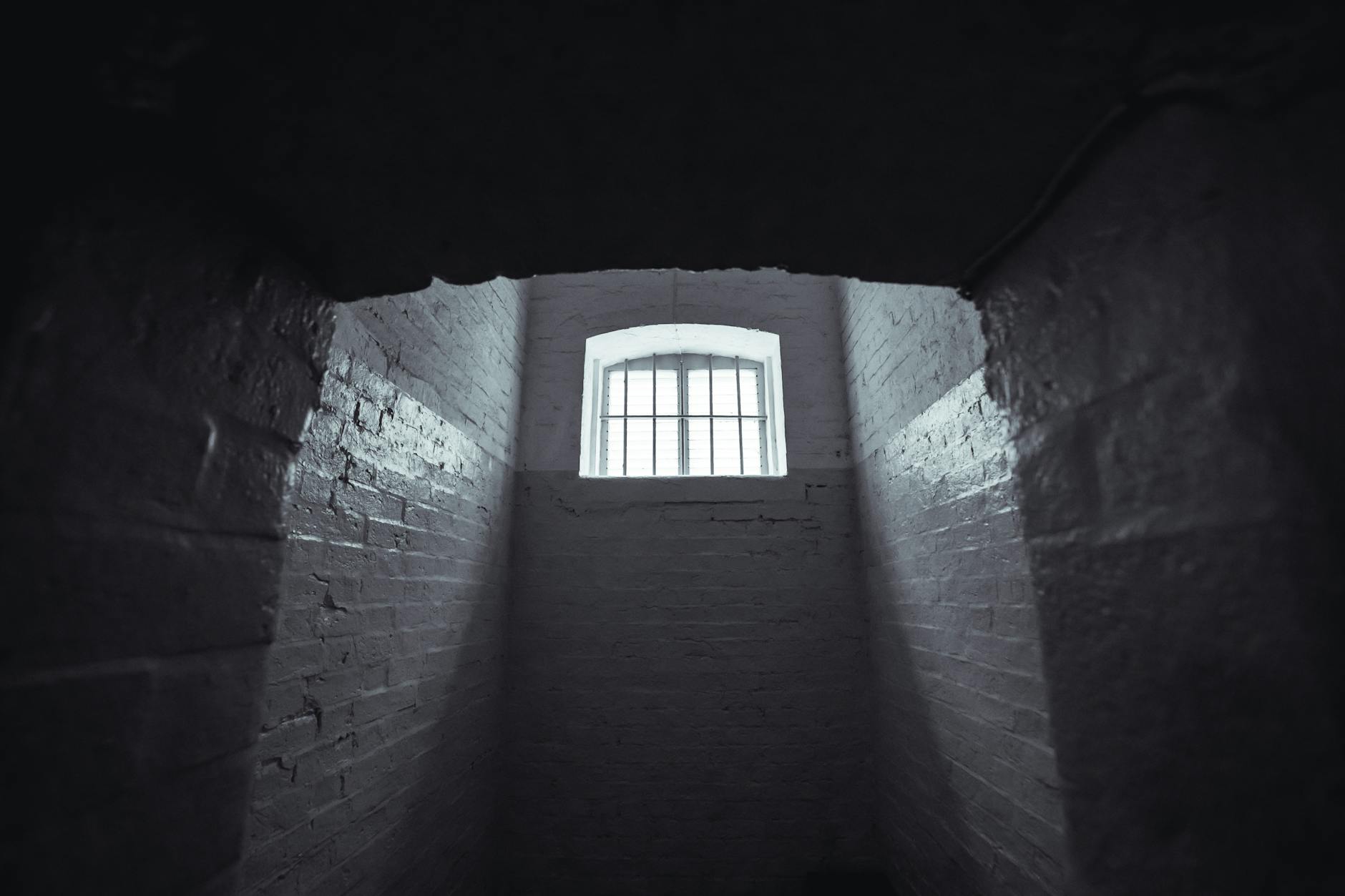

For years, survivors of domestic violence, coercive control, and sexual assault have lived in fear while their abusers walked free under promises that were never kept.

These new measures offer a glimmer of hope. But hope alone isn’t enough—not without enforcement, accountability, and a justice system that truly understands what victims live through while waiting for justice to arrive.

The New Reforms: What’s Changing

The Carney government’s plan aims to strengthen bail and sentencing rules for violent and repeat offenders by:

- Introducing reverse-onus bail, requiring serious offenders to prove why they deserve release.

- Allowing consecutive sentencing so multiple crimes mean multiple punishments.

- Restricting conditional sentences for sexual and violent offences.

- Investing $1.8 billion to hire 1,000 new RCMP officers and improve enforcement.

- Working with provinces and territories on root causes like mental health, addiction, and housing.

Carney said:

“In Canada, you should be able to wake up, get in your car, drive to work, come home, and sleep soundly at night. When laws repeatedly fail to protect those basic rights, we need new laws.”

For those of us who have spent years living with fear instead of peace, those words matter.

What Consecutive Sentencing Really Means

When politicians talk about “consecutive sentencing”, it sounds technical.

But to victims and their children, it’s the line between real justice and none at all.

Let’s look at what that actually means using my own situation as an example—assuming the maximum possible penalties under the Criminal Code of Canada, before any plea deal or time-served credit.

Scenario: Maximum Sentences if Served Consecutively

| Offence | Criminal Code Section | Max Penalty | Count | Total if Consecutive |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sexual Assault | s. 271 (basic) – up to 10 years, or 14 years if aggravated (s. 273) | 1 | 10 – 14 years | |

| Breach of Police / Court Conditions | s. 145(5) – up to 2 years per breach (indictable) | 3 | 6 years | |

| Assault on a Child (Under 16) | s. 266 / s. 267 – up to 5 years per count | 2 | 10 years | |

| Uttering Threats to Cause Death or Bodily Harm (to a Child < 16) | s. 264.1(1)(a) – up to 5 years | 1 | 5 years |

Total Maximum if Sentences Run Consecutively:

→ 31 – 35 years imprisonment

(He will likely plea deal—but this shows the maximum legal accountability.)

The Reality—Concurrent Sentencing

Under current Canadian sentencing practice, judges almost always order sentences to run concurrently, meaning at the same time, not one after another.

When that happens, the sentence for multiple crimes is effectively capped at the length of the longest single offence.

In this case:

| Offence | Max Penalty | Served Concurrently With | Added Time |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sexual Assault | 10 – 14 years | — | 10 – 14 years total |

| Breach of Conditions (×3) | 2 years each | Served concurrently | 0 additional years |

| Child Assault (×2) | 5 years each | Served concurrently | 0 additional years |

| Threats to Children (< 16) | 5 years | Served concurrently | 0 additional years |

Total Sentence if Concurrent:

→ 10 – 14 years total

That’s it.

Even with six separate offences—sexual assault, assaults on two children, three breaches of police conditions, and threats to kill—the system would treat it all as one blended sentence.

Where Is the Children’s Justice?

This is what “concurrent sentencing” really means in practice:

the crimes against the children—the assaults, the threats, the fear—would add zero extra jail time.

So while the headlines might say “multiple convictions,” the reality for victims is that those convictions don’t count.

The law’s math erases their pain, their voices, and their right to see accountability reflected in the outcome.

Each of those children will carry that trauma for life.

Yet under concurrent sentencing, the system acts as if their experiences never happened—as if the harm to one child somehow covers the harm to another.

That’s not justice.

That’s bookkeeping.

Why Consecutive Sentencing Matters

Consecutive sentencing doesn’t just increase time served—it restores meaning to the word justice.

It tells every survivor, every child, and every community that each act of violence matters on its own.

That safety isn’t negotiable.

That we count every wound, not just the first.

Because when sentences overlap, victims disappear between the lines.

Political Voices and Public Debate

Supporters

Government MPs describe this as restoring public trust and protecting communities. Police unions call it a long-needed fix to keep violent offenders off the streets.

Critics

- Larry Brock (Conservative MP and Justice Critic) argues the reforms “don’t go far enough” because the principle of restraint still requires judges to impose the least onerous conditions: “You can’t put a criminal halfway in jail; halfway measures won’t end the scourge of crime and disorder in our communities.”

He warns that without repealing that principle, victims will remain unsafe. - The Canadian Civil Liberties Association counters from the other direction: “There is no evidence that bail causes crime. Law-making absent evidence can’t help but be good law.”

They fear automatic restrictions could erode fairness and judicial discretion.

Both sides reveal the same truth: doctrine and delay are the real barriers.

Beyond Canada: The UK’s Domestic Violence Crisis

This isn’t just a Canadian issue.

In the UK, a Channel 4 investigation and the Domestic Abuse Commissioner’s 2025 review found that 87 percent of family-court child-arrangement cases included evidence of domestic abuse—yet more than half still granted unsupervised contact to the abusive parent.

Commissioner Nicole Jacobs said:

“No child should be forced to spend time with an abusive parent. But time and time again, the pro-contact culture and antiquated views on domestic abuse put children in harm’s way.”

One mother was even told she could face jail if she refused to facilitate contact between her child and the man who raped her.

Different country, same problem: a system designed to prioritise legal ideals over lived safety.

By contrast, I was fortunate that my most recent experience in the Canadian courts went differently. At an emergency hearing my ex brought to demand 50 percent access to our son, the judge threw out the request. He recognised several key facts: that my ex is facing serious criminal charges, and that my actions were rooted entirely in protecting my child’s safety. I had already offered supervised community access—three hours a week for park visits, swimming, or museums—so our son could still have some contact without being exposed to unsafe environments or private homes.

It shouldn’t take luck to get a judge who sees that distinction, but I was grateful he did.

My first lawyer, however, wanted me to compromise on my son’s safety in exchange for securing travel consent for my daughter. When I refused, he told me I was being difficult, argumentative, and unwilling to negotiate.

Damn right I was.

Some things are a hard no—and negotiating a child’s safety is one of them.

When that lawyer refused to help me, I went to court on my own and won the emergency motion for my daughter’s travel consent. It was exhausting, but it proved something I’ll never forget: sometimes you have to stand alone to stand up for what’s right.

That experience showed me both sides of our justice system: the rare moments when a judge gets it right, and the many ways doctrine, procedure, and even some lawyers still fail victims who refuse to compromise on safety. The justice system—from its outdated doctrines to the professionals who apply them—needs a complete overhaul.

When These Laws Were Written

To understand why our legal doctrines no longer fit reality, we have to go back to when they were created.

The foundational ideas behind Canada’s bail and sentencing system were written into law more than a century ago—based on 19th-century English common law. When the Criminal Code of Canada was first enacted in 1892, criminal cases moved through the courts quickly, and bail was designed to protect against wrongful detention, not prolonged uncertainty.

At that time:

- Most criminal trials took place within weeks or a few months of arrest.

- The average pre-trial jail time for those detained was under 30 days.

- Judges could safely presume that if someone was released on bail, their case would be resolved soon after.

Even through the mid-20th century (1950s–1970s):

- Serious criminal trials typically took 6 to 12 months.

- The presumption of release still made sense because justice was relatively swift.

But that world no longer exists.

Today:

- The average time to trial for indictable offences in Canada is 18 to 30 months, and for sexual assault or domestic violence cases, it can take three to five years.

- Complex cases involving multiple breaches or overlapping criminal and family court matters can stretch even longer.

- Most accused are out on bail during this period, often breaching conditions without real consequence.

| Era | Average Time from Arrest to Trial | Pre-Trial Jail Time (if detained) | Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1890s–1930s | Weeks to a few months | Typically < 30 days | Small caseloads, local courts, few procedural delays |

| 1950s–1970s | 6–12 months | Often 1–3 months | Still relatively swift; presumption of innocence workable |

| 2000s–2020s | 18–60 months | Rarely detained that long; most on bail | Complex cases, Charter rights, disclosure delays, court backlogs |

| 2025 (current) | 2–5 years (avg. for domestic/sexual violence) | Most released on bail with minimal supervision | Victims live with ongoing risk and uncertainty |

The doctrine of innocent until proven guilty was never designed for a world where justice moves this slowly.

It was meant for a system that could deliver verdicts in weeks—not years.

Now, the same principle that once protected liberty has become a shield for repeat offenders, leaving victims to live under ongoing threat while the system drags its feet.

Time as a Weapon

“Innocent until proven guilty” is essential—but it was written for a world where trials happened within months, not years.

In the 1800s, justice was swift; the accused was either convicted or cleared quickly.

Today, victims of domestic or sexual violence often wait 2 to 5 years for trial. During that time, the accused may live freely under minimal restrictions, while victims remain trapped in fear.

Justice delayed isn’t just delayed—it’s lived as trauma.

A system that refuses to adapt its timelines to modern caseloads turns doctrine into danger.

If we reform bail but ignore trial delays, if we promise safety without funding enforcement, we change the words but not the outcome.

What Real Reform Looks Like

- Rebuild doctrine around safety, not convenience.

- Integrate trauma-informed training for judges, Crowns, and police.

- Create national standards for trial timelines in violent and sexual offences.

- Enforce breaches immediately and transparently.

- Invest equally in prevention, enforcement, and recovery.

This is how we fix a system—not by patching holes, but by redesigning the foundation.

Enough Politics—Start Governing for Canadians

There comes a point when political colours stop mattering.

Victims don’t care whether protection comes from a Liberal bill or a Conservative motion—they care whether the system keeps them safe.

It’s time for Parliament to stop saying “Liberal this” and “Conservative that” and start saying:

“We, the Canadian Government, will fix this.”

Justice should not be a partisan performance.

It should be a national commitment—to safety, fairness, and dignity for every Canadian.

Because abuse doesn’t ask who you voted for.

It only asks who still has power.

And as long as politicians fight each other instead of fighting the problem, abusers keep winning.

Final Reflection

Mark Carney’s reforms are a step—a real one—in the right direction.

But steps alone won’t reach justice.

The truth is that sentencing in Canada almost never approaches the maximum penalties written in law.

Outcomes are often shaped by plea bargaining, charge reductions, and judicial attempts to keep sentences under two years, so offenders serve time in provincial facilities instead of federal prisons.

It’s a quiet form of leniency built into the system itself—one that too often erases the scale of harm and the seriousness of the crimes.

We need unity, urgency, and honesty.

We need laws that evolve with time, doctrine that values safety, and leaders who work together for the people they serve.

Change has begun.

Now, it’s up to all of us to make sure it doesn’t stop here.